PDF version: https://saveoursbs.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/A-perspective-for-funding-the-SBS-in-the-2012-15-triennium.pdf

Sent by email to:-

Hon Senator Stephen Conroy, Minister for Broadband, Communications & Digital Economy

Executive Summary — a perspective for funding the SBS in the 2012-15 triennium

In late 2006 SBS introduced in-program advertising. Advertisers replaced viewers as the clients of SBS, while viewers became a product to be on-sold to advertisers. Ratings became important. Adjustments were made to appease advertisers. This fundamental change has mobilised a ground swell of electors seeking government funding for the SBS specifically to reverse the above.

- SBS has a unique role in Australian society and an increase in funding is justified for several reasons related to the above. These are detailed in this submission.

- Income from advertising as a major source of revenue for SBS combined with government funding has not been sufficient for SBS to keep up with the financial pressures brought upon it by multi-channels. SBS’s gross television advertising revenues decreased in 2010-11 and overall revenues have not kept pace with increasing operational costs.

- In 2010, SBS announced its Social Inclusion and Cohesion Policy which is in step with the Federal Government’s Social Inclusion Principles. The implementation of the SBS social inclusion policy requires substantial government funding. This policy lays the foundation from which SBS can develop its practices, understandings, programming and other policies.

- Although SBS is smaller than the ABC it is disproportionately underfunded. The output of the SBS is comparable to at least half that of the ABC, but its base funding is far less.

This submission discusses the above with funding options to phase out in-program breaks.

- A reduction of in-program breaks from the current number, while still allowing one only in-program break per program (plus the break between programs) may be a low or no cost step towards ultimately phasing out in-program breaks.

- Although it would be highly desirable that funding be provided in full to the SBS for the specific purpose of the removal of disruptive breaks at the commencement of the 2012-15 triennium, it may be possible to stagger the amount requested over three years, or defer a smaller amount for a lesser period later in the triennium, to a period of government surplus.

Even in times of a fluctuating economy, a significant increase in public funding for SBS is justified for maintenance, expansion of services and the winding down of in-program breaks.

Committee of Management

Save Our SBS Inc

11 Oct 2011

Social investment for the future – 2012-15

The Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) is established under the SBS Act and its purpose is guided by its Charter; the umbrella statement of Australia’s multicultural broadcaster[1].

SBS is a microcosm of society not just on-air, but internally in its day to day operation. Few public organisations foster multiculturalism, diversity and social inclusion to the extent that SBS does. The peoples of SBS and its contributors may take credit for nurturing much of this, and often with fewer resources than other broadcasters.

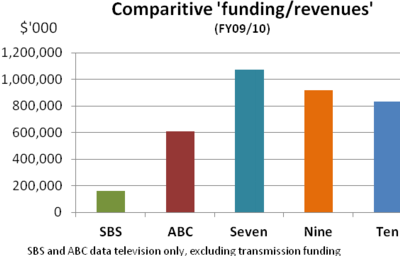

- In 2009-10, SBS total revenue was less than ¼ for that of the average Australian commercial network. This includes government support and income from commercial activities, including advertising.

- In the same year the total revenue for the SBS (from all sources) was $308.4 million[2].

- The average advertising revenue for each of the three free-to-air commercial TV networks was $1,231 million[3], or about four times the revenue for all SBS output, including its television, radio and internet services.

- For the 2009-12 triennium SBS received less than ¼ of the funding that the ABC received from the public purse[4].

- Funding for SBS television is as little as one sixth compared to the highest commercial network annual budget[5].

By every measure, SBS was the least funded broadcaster in the period mentioned.

GRAPH 1: Comparative ‘funding/revenues’ by broadcaster/network (click image to enlarge)

Such lack of financial resources encouraged the SBS to seek additional funds through advertising.

In 2010, SBS actively sought to move in a new direction, although not able to rid itself of its commercial approach. After months of community consultation the SBS Board, under the Chairmanship of Joe Skrzynski, announced the SBS Social Inclusion and Cohesion Policy[6]. This move can only be applauded and is the right policy for SBS[7]. It recognises and takes into account the diverse mix that makes up the Australian society; a world example of multiculturalism and ethnic communities living within the one country. SBS’s Social Inclusion and Cohesion Policy is on the back of their Second Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP)[8] which is SBS’s policy and practice about increasing awareness of the contribution of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander communities to Australian society and building capacity to learn from and serve Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The SBS Social Inclusion Policy is in step with the Federal Government’s Social Inclusion Principles[9] announced earlier this year. This is part of a whole of government policy and the release of the federal government’s booklet, Australia’s Multicultural Policy — The People of Australia[10] published February 2011, articulates that. The SBS social inclusion and cohesion policy will build on those principles and if the SBS is properly funded, not only will it flourish but it will reflect the government’s goal that “reaffirms the Government’s unwavering support for a culturally diverse and socially cohesive nation” (Chris Bowen, Minister for Immigration, and Citizenship; &, Kate Lundy, Parliamentary Secretary for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs[11]).

This policy is the foundation of SBS, from which its practices, understandings, programming and other policies may develop. However the ongoing implementation of the SBS social inclusion policy requires substantial government funding. The policy may be at risk of failure without such. If that occurred that could be to the detriment and worthiness of the SBS policy direction and would also undermine the desire of the government’s social inclusion and cohesion policy and principles referred to above.

Funding, social inclusion & cohesion, and advertising

The expansion of multi-channels in the commercial sector particularly, added to financial difficulties for SBS. There are now 16 free-to-air television broadcasters in capital cities (ABC has 4 channels; SBS, 2 channels; community, 1 channel; SEVEN, three channels; NINE, three channels; and, TEN, three channels) compared with a few years ago, when there were then only six. The increased numbers of channels has seen revenue for SBS from television advertising drop and continue to drop. It is now below that of 12 months ago (excluding the impact of the World Cup). Predictions by SBS are that it will decline further[12]. At best, any financial success could only be described as transient and limited to a period of the few years just concluded. Income from advertising as a major source of revenue for SBS will not be sustainable.

“the explosion of multichannels from commercial broadcasters . . . has doubled the amount of commercial inventory in the market and [this] is having an impact on the revenue that SBS can derive.” (SBS, MD, Sen. Est. 2010)[13]

The above is not surprising as when in-program advertising was introduced in late 2006, SBS stated that that model would only be sustainable for 10 years at the most. At that time SBS had not considered, and was not to know that only a few years later, the ‘competition’ would almost triple. SBS had always said that governments would need to decide on how SBS was to be funded in the longer term. The time to look at the longer term is now. It has arrived sooner than the presumed 10 year span referred to, probably due in part to multi-channels and partly as a spin off from the (excellent) whole of government social inclusion policy (as practised by the SBS). This will be discussed later.

Government funding combined with revenue from advertising has not been sufficient for SBS to expand. In 2008 we reported that revenue for SBS was significantly lower than Australian commercial broadcasters and the ABC[14]. That remained the case despite the increased government funding in the 2009-12 triennium.

The combination of the above has resulted in changes at SBS that could not have been imagined or anticipated 20 or more years ago. The ‘experiment’ since 2007 being the commercialisation of the broadcaster questioned the unique and “special” nature of the SBS[15] [16].

Since late 2006, SBS has juggled between two masters: advertisers and audience. However the two are not always compatible. An analysis of this reveals difficulties at a number of levels. These points shall be expanded upon in this submission and recommendations provided.

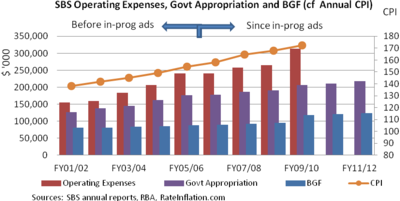

Since 2001, with the exception of that appropriated in the 2009-12 triennium, the average increase in BGF was 1.5 percent per annum[17]. This was below ordinary inflation and well below that required for a functioning broadcaster, let alone a broadcaster that might hope to expand its services or reduce its reliance on advertising. The policy that saw the introduction of in-program advertisement breaks on SBS-TV, was an attempt to offset the relatively low increases in base government funding (BGF)[A].

GRAPH 2: Derived from data presented in a series of SBS Annual Reports[18] and published inflation data[19] (click image to enlarge)

GRAPH 2 illustrates that the gap between base government funding and government appropriation has increased since 2001. It also shows that the government appropriation is well below the actual operating expenses of SBS.

In the period mentioned on GRAPH 2, public monies appropriated by SBS, although calculated in accordance with WCI6 [20], have not kept pace with the actual operating costs of SBS. As a result, BGF for SBS was not fully indexed to account for all price rises (outside the WCI6 calculations), in particular increasing content costs. In short this led the SBS to look for ways to make up the shortfall, which it has done in part by disrupting programs for advertisements as a means of attracting more advertisers. However often this was at the expense of the viewer. The full impact of the commercialisation of Australia’s multicultural public broadcaster came into force in 2007 and has remained the case since.

Without a doubt no-one enjoys disruptions into a program, particularly on a public broadcaster, and, especially in a position where the maker of the program had not intended a break be placed. The jarring impact of such informs the accusation that SBS is ‘forcing’ a break into the program for the benefit of the advertiser and not the viewer. This undermines the Charter by morphing the production of the program and leads to diminished viewer experience. This is the point at which a hybrid broadcaster may be perceived as crossing the line to that of a commercial network. The loyalest of viewers and strongest supporters of SBS have voiced objections. Although understanding of the reasons, that is, the underfunding position of the SBS, the resulting consequences – the intrusion into programs for advertisements, remain offensive to viewers and advocates of what an Australian public broadcaster ought to be[21]. However this situation is solvable.

Such wide disapproval of a public broadcaster disrupting programs for commercial breaks is shared almost universally amongst the public at large, politicians of all persuasions, SBS staff and Board, and if it were not for a potential shortfall in revenue, the disruptions on SBS television may have been removed. A solution publicly articulated by the SBS Chairman, Joe Skrzynski is paraphrased here.

If government has enough money to buy out the advertising, that may be an option for the future[22].

A solution would be to significantly increase public funding for SBS possibly in stages in the 2012-15 triennium and simultaneously wind down the number of in-program breaks with the aim of eventually phasing out all advertising on SBS in the longer term, or at least restricting them to between programs by early 2015, a period when presumably Australia’s finances be stronger.

Acknowledging that in-program breaks would not exist to the extent they now do if the SBS had operated within the intent of the Parliament of 1991 (when the SBS Corporation was formed under the Act), ought not to detract from a significant increase in public funding for the SBS.

The intent and understanding in debating the SBS Bill (now the Act) in 1991, was that advertisements would “top and tail programs”, except during the natural break of a sporting event.

1991 Parliament understanding of a “natural program break” for the SBS bill (now the Act)

“half-time in a soccer match” (Mr Smith Liberal)[23] – the only example given [and]

“in effect what will happen is that advertising will top and tail programs”

“let us not try to get the advertising revenue that will make the SBS another commercial channel. If we do, again, that will change its character, and I do not think that is really what we are about” (Mr Sinclair National)[24]

“advertisement–at the beginning and the end of the sponsored program. In that way the viewers were not disturbed and were not constantly interrupted, as is the case on some of the commercial television programs” (Mr Lee Labor)[25]

Section 45 of the SBS Act states that SBS may broadcast advertisements during “natural program breaks” but the Act fails to define that phrase — although the intent of the Parliament is well documented in Hansard [26] (see quote box above & references). The current definition — contained in the GUIDELINES FOR THE PLACEMENT OF BREAKS IN SBS TELEVISION PROGRAMS[27] (which does not take account of intent) — was determined by SBS in 2006 and reaffirmed in 2010[28]. This SBS definition was described as being: “inconsistent with the intent of the limits that the legislation attempted to set” and not in accordance with the people who were involved in the drafting of the SBS Act (Senator Conroy) [29]. However, none of these differences detract from the need for greater public funding.

The dangers of a public broadcaster taking the commercial path, whether by necessity or desire, were documented as a tendency of the broadcaster to move away from its Charter in order to satisfy its clients, the advertisers.

An overview of the market and advertising research reports carried out for SBS . . . confirms anecdotal accounts of the effects of advertising culture on SBS programming . . . that it has had a profound effect on the broadcaster in shifting the orientation of SBS away from the terms of the Charter and towards satisfying market conditions. One of the dominant criticisms . . . was the appropriateness of a public service broadcaster being so led by community attitudes; when its Charter quite clearly requires it should instead be leading the community in attitude change[30].

However the fine balancing act that SBS struggles with, program and Charter requirements versus advertisers offering further funding is not without problems. The attraction to a greater financial certainty has not been assured to SBS by its dependency on advertising.

Cost of removing commercial breaks

The cost of removing advertising or even partly removing in-program breaks can be divided into three broad categories: financial, perception, and social inclusion.

Financial

Revenue from television advertisements accounts for almost all of total advertising revenues on SBS.

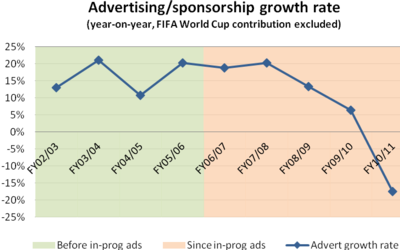

There was a steady increase in revenue from advertising from 2001 to 2010. Although the year by year dollars increased with each year, the rate of growth slowed towards the end of this period. Post 2010 revenue growth from television advertising was negative.

Income from advertising for SBS was $23.6m in 2001-02 (excluding FIFA World Cup revenues). From then up to 2005-06, the rate at which advertising grew was 16.8 percent per annum# [B] [31]. This is the period in which SBS-TV did not disrupt programs and placed advertisements between programs only[C]. In the first year of full on in-program advertising (2007), both ad revenue and its rate of growth increased a little. However from 2008 to 2010, the overall rate at which advertising was growing fell to 13.4 percent per annum then lower[32]. SBS attributed the decline to the explosion of multi-channelling[33] although apparently the overall numbers of people watching free to air television grew since the introduction of multi-channelling. “Free TV’s share of prime-time viewing is up”[34]. The industry ratings company OzTam[35] showed ratings for SBS television hovered steady in the 4 to 6 percent range in the years 2006 to 2011 (5.4 percent[36] for first half of 2011).

In October 2010 SBS predicted forecasts to FY ending 2015 were that the growth rate of revenue from advertising will fall.[37] [38] This confirms SBS’s earlier statements that advertising is not sustainable in the longer term.

GRAPH 3: Rate of growth of advertising from 2002 to 2011[39] [40] (click image to enlarge)

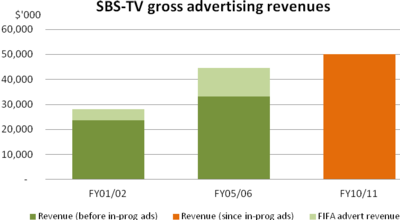

A snapshot of three time points at the beginning, middle and end of the past decade is useful. Gross revenue from advertising in 2001-02 was $23.6m[41] (excluding revenues from the FIFA World Cup). By 2005-06 the total advertising revenue was $46.5m[42]. Of this, $33.2m[43] came from television only advertising (when programs were not interrupted for advertising) and the FIFA World Cup generated a further $11.39m[44] in that year. In 2010-11 total television advertising revenue for SBS was $50m[45] (when programs were disrupted with commercial breaks).

GRAPH 4: Snapshot of advertising revenues from 3 time periods from 2001 to 2011[46] [47] [48] [49] [50]. The two green bars on the left of the chart are when adverts were between programs (past policy). The amber bar on the right (current policy) is with in-programs ads. (click image to enlarge)

Other factors affecting advertising revenues are documented below.

The number of people employed to sell airtime in 2001 and 2006 at SBS was a fraction of the 2011 levels engaged for the same purpose.

At the same time that the SBS changed to the new (now current) model to allow in-program advertising, more people were engaged to sell advertising. Also at the same time SBS ‘relaxed’ its policy on the type of advertisement it was prepared to accept[51] [52] [53] [54]. Under the new model, almost any type of advertiser became acceptable.

SBS charged the same amount for advertisements regardless of whether they were placed between programs or in-programs[55].

Was it the decision to accept almost any type of advertisement, or the expansion of people selling advertising for the SBS, or the shift to insert commercial breaks into programs, that affected SBS advertising revenues? The precise answer may never be known, short of conducting a trial that reverts to placing breaks between programs only for a period, while still accepting a wide range of advertisers and retaining ample numbers of people in air time sales.

Under the old model where ads were between programs only, advertisements in breaks of 8 minutes duration were sold with a 50% discount to the advertiser[56]. This statement implies that the move from the old, to the current model of short breaks in-program[57], did not apply a discount to the current break length, which is usually under three minutes.

If programs were no longer disrupted for ad breaks, SBS had estimated a potential shortfall of $29.39m to $35.72m[58] but more recently increased that to $36m[59] then $45m[60]. The methodology for these calculations was not publicly revealed. (SBS stated the $45m would not cover the ‘big’ sporting events, e.g., La Tour De France & FIFA World Cup Series; that these programs would therefore need to carry in-program commercial breaks).

Although it may be said with certainty that a rescheduling of advertisements from in-program to intra-program would be less costly to the tax payer than would a total ban on all advertising, the accuracy of any estimation to reschedule advertisement breaks from in-program, to between program only, may only be confirmed after implementation. In terms of actual costs, a more pertinent point arising out of the above is how to proceed in the direction of shifting advertising from in-program to intra-program, as a step towards that intended by the 1991 Parliament when SBS was corporatised[D]. If acknowledgment of the 1991 intent were to be resumed (to that practised pre-late 2006), essentially the SBS has suggested an increase of their base government funding of $45m for that specific purpose — this being separate from other monies for maintenance and expansion of services.

Although it would be highly desirable that funding be provided to the SBS for the specific purpose of the removal of disruptive breaks at the commencement of the 2012-15 triennium, it may be possible to defer same to a later period in the triennium — to a period of government surplus, for example if the action commenced in the last quarter of the final year of the triennium, then the base government funding would need to be increased by $11.25m[E] ($45m ÷ 4) in the 2014-15 year for a change effective on 1 April 2015.

If the number of in-program breaks were to be reduced to one only per program, such may be also be a low or no cost approach to eventually rescheduling break content from in-program to intra-program.

Perception

An international survey of public service broadcasters (PSBs), commissioned by the BBC and conducted by McKinsey and Co, argued that the presence of a public service broadcaster in a broadcasting ecology consisting of both commercial and public service broadcasters:

. . . combines creative and market pressures on broadcasters to achieve society’s aims for its broadcasting market.

It does so by setting off a ‘virtuous circle’ with its commercial competitors. Because of its unique role and funding method, a PSB can popularise new styles of programming, and thereby encourage commercial broadcasters to create their own distinctive programs. In this way the viewing standards of the entire market are raised.

Many PSBs are funded, at least partly, through advertising. Our survey shows clearly the potential dangers of this approach. We have found evidence that the higher the advertising revenue as a proportion of total revenues, the less distinctive a public service broadcaster is likely to be[61].

The McKinsey survey concluded that the greater the advertising income that a PSB received, the more it looked like a commercial broadcaster and the less is looked like a public service broadcaster. There is evidence of this with SBS.

The introduction of in program advertising to the SBS in effect makes the SBS a de facto fourth free-to-air commercial television station and serves to erode the fundamental tenets of public broadcasting- that is, that it should be free from commercial and political influence.[62]

The universal dislike of in-program breaks on SBS television and the perceived and actual crossing of the line into that of a commercial operator have made it difficult for all.

The Charter of the SBS speaks to the output of the SBS. In essence the Charter includes the entire packaging of the SBS – not just the program content — and the manner in which SBS television in particular presents itself, now like that of a commercial broadcaster, led viewers to think of the SBS as deviating from its “special” purpose. This is disturbing even for a hybrid public broadcaster.

The SBS places two breaks in a half hour television program plus a break on conclusion of the program. This therefore means that when 2 half-hour programs are scheduled back to back, there are in fact 6 breaks in total for that hour of viewing. This is little different from commercial broadcasters who schedule 5 in-program breaks in a one hour program slot

This comparison above is intriguing as the SBS is restricted by legislation to 5 minutes of advertising per hour, whereas the commercial stations have no such restriction and typically run around 13 minutes[F].

The presentation of the SBS is not distinguishable from that of commercial television.

Presenting itself as a commercial broadcaster, the SBS has suffered despite multicultural broadcasting being a most valuable asset to the Australian society. Lack of sufficient government funding is the real issue and the one thing that could change all this.

In 2007 some 1,119 people emailed politicians seeking more funding for SBS and legislative restrictions to prevent disruptions into programs[63].

In 2008 more than 7,500 people requested an end to the disruptions into programs by an amendment to the SBS Act coupled with full funding for the SBS[64].

In a small study conducted when SBS had been interrupting all television programs for just on two years, 96.3 percent of the 1,733 participants said they wanted “SBS-TV to stop interrupting programs for commercial breaks” and 95.9 percent said they wanted “government to legislate to prevent programs from being interrupted on SBS-TV”[65].

In 2008, more than one-thousand public submissions were made to the DBCDE ABC SBS Review and it is interesting to note that of those that commented on the SBS only, almost all expressed the view of wanting the government to legislate to prohibit SBS from interrupting programs for commercial breaks[66] [67].

By 2010 more than 15,400 had directly asked their parliamentarians to increase public funding for SBS so that it would be free from advertising, to amend the SBS Act accordingly, saying – an investment in SBS would be an investment in Australia’s future cultural diversity[68]. By any measure there is a ground swell of electors who wish for all of these things.

Social inclusion

Prior to late 2006, when advertisements were outside programs, the viewer was very much the client of SBS and SBS considered the needs of their client, the viewer — over and above that of an advertiser. However from 2007 when SBS began to disrupt all television programs for advertisements, the client of SBS changed. It became the advertiser. Viewers of any commercial broadcasting transaction are in fact a commodity, a product, to be sold to the advertising client. This highlights one of the main differences between a commercial operation and a public service broadcaster.

In the years that advertisements were not placed within SBS-TV programs, the product of SBS was clearly the actual program content. However, when SBS began to interrupt programs for their advertiser, the product became the viewer, who is now onsold by SBS to the newer client of SBS, the advertiser. This is the point where the hybrid nature of SBS was ‘forced’, due to inadequate public funds, to cross the line and be more like that of a commercial broadcaster.

The increased reliance on income from advertising (from 2007 to the present time), evidenced by the disruption into SBS television programs for commercial breaks, has not been without problems. Financially it was not as expected. Moreover the disruptions have annoyed viewers[69] [70] [71] the most noticeable impact being the expansion of commercial breaks into SBS-TV.

However this approach, by the very purpose it seeks to serve (to raise funds for local productions) undermines that of social inclusion because the client of SBS television has now become the advertiser, not the audience. Daily minute by minute ratings have become the norm; necessary to make adjustments to appease the advertiser. The audience is now the product that is sold to the client, the advertiser. This was not the case prior to 2007, when advertisements were placed between programs only. Then, the more distinct separation of commercials away from programs meant that the program remained the product and the audience the client with the net result of a more socially inclusive broadcaster. The current situation can only be reversed if the following triple action occurs:- a legislated phasing out of commercial disruptions into SBS television programs coupled with proportional increases in government funding and further public money for expansion of services[72].

Save Our SBS strongly recommends the foregoing. SBS shall then be freed from the constraints it currently faces, switching the focus of the client of SBS from advertiser back to the audience, thus fostering social inclusion to the full extent. This is entirely appropriate in consideration of the whole of government approach for a national multicultural and social inclusion policy[73] [74] [75].

In the light of that very worthwhile policy, it would be risky for government to send the wrong message to the SBS and leave it to face commercial competition[76] [77] [78]. That will happen without sufficient government funding. Such would be to deny the whole of government policy referred to.

While programs remain disrupted for commercial breaks, SBS will be at risk of proceeding down the path that economists call the Principle of Minimum Differentiation.

. . . stations based on advertising revenue will seek to maximize their audience (and thereby their revenue). Stations will therefore duplicate program types as long as the audience share obtained is greater than that from other programs.

Hence a number of stations may compete by sharing a market for one type of program (such as crime dramas) and still do better in audience numbers than by providing programs of other types (such as arts and culture). In economics this point is an application of the Principle of Minimum Differentiation, a principle also capable of explaining such associated phenomenon as why bank branches may cluster together, why airline schedules may be parallel, and why political parties may have convergent policy platforms[79].

The introduction of in-program breaks in late 2006 is a form of the above. By its nature, it reaffirms the status quo – like that of the commercial broadcasters, disrupts in the same manner, opposes diversity of presentation[G] (as does 7; 9; and 10), and conflicts with the principles of social inclusion.

The original purpose of in-program advertising was a promise that the revenue from advertising would be used to “increase the production of Australian multicultural drama and documentaries”[80]. That did not always happen. In 2009-10 none of the $22.7m advertising revenue from major sporting events was used for such purpose[81].

When addressing the question as to why or if the SBS should be focusing on using advertising revenues for operational purposes or to increase local productions, a presumption is sometimes put that the SBS was intended to incur less expenses than other broadcasters, for example the ABC. It has sometimes therefore been argued that it would be inappropriate for government to fund the SBS for a withdrawal of ads or even a reduction of the intrusive in-program breaks. However if the ‘SBS was intended to incur less expenses than other broadcasters and therefore receive less government funding’ argument is taken to its logical conclusion, it would also follow that SBS ought not be attempting to produce local productions to the extent that occurred over the past five years, in which case the original purpose of the need to run in-program advertising must also be questioned. Undoubtedly if there were fewer Australian productions, there would be less of a need to raise such revenues in the manner practised; i.e., from disruptive advertising breaks. However such discussion would have to be part of a separate discussion about the purpose of the SBS.

The above highlights an outcome resulting from inadequate funding from the public purse.

Funding

When the SBS Corporation was formed in 1991, it was never envisaged that SBS would have taken the commercial path it commenced in late 2006. In 1991, that was not intended. Then, it would have been inconceivable to think of a need to address advertising matters to the extent done here.

Save Our SBS would like to see all advertising removed completely from SBS. We acknowledge however that the SBS is permitted to carry restricted advertising. We also note the original intention of the parliament as recorded in the Hansard[82] was that – except for sport – programs would not be disrupted (see earlier discussion about this) and that the Act endeavoured to convey that[83].

As to funding, the following possibilities ought to be considered:-

- The funds ‘saved’ from the switch-off of the analogue transmitters be appropriated to SBS; hence an increase in the base funding would eventuate even though total government appropriation would remain steady.

There is however a strong case that SBS be funded above and beyond any ‘savings’ funnelled back to SBS even if the above were implemented.

- A portion of all revenue raised from the fees of the commercial broadcaster licensees be destined directly for the SBS, in addition to the ordinary triennial funding of government appropriation.

The airwaves are public and it follows that the for-profit commercial use of them ought to be in exchange for direct benefit to a public broadcaster.

During the phase in period of multi-channelling the commercial broadcasters were assisted to the extent of $250m by having their license fees waived for two years. This enabled the commercial broadcasters to develop their second and third channels. SBS has claimed that it has had a downturn in its ability to generate advertising revenue directly due to multi-channelling. Fees raised from the commercial broadcasters could be ear marked for the SBS, as outlined in the dot point above.

Expansion of services

Due to its low levels of funding, SBS has not had been in a position to keep up with other comparable services . Funding would be required to implement the items below. This would allow SBS to ‘catch up’ with how modern media organisations operate, through:-

- Development and expansion of SBS’s internet services.

- Expansion of other television channels.

- Expansion of digital radio.

- Expansion of indigenous broadcasting.

- Funding for innovative multiculturally relevant programs in an Australian context.

With increased government funding there could be relevant opportunities for Australia’s culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities too, for example:-.

- Expansion of news services relevant to communities from an Australian perspective.

- Expansion of audio language services to those areas not currently serviced.

- Improvement of migrant representation in media and language skills including English language tuition.

- Expansion of local content to convey multicultural Australian stories.

- Expansion and development of mobile internet services including apps across every platform.

- Establishment of an SBS archiving service.

- Funding for languages other than English (LOTE) productions, both imported and produced locally.

- Development of the SBS music language services that connect with younger migrant audiences such as digital audio broadcasts (DAB), podcasts and associated internet apps.

- Development of online news services.

- Journalistic opportunities for people of non-English speaking backgrounds.

The above are all worthy of investment and at various times have been publicly flagged as out of reach for SBS in the absence of a significant increase in public funding[84]. Similarly low levels of public funding have meant that SBS broadcasts less Australian content compared to its peers[85].

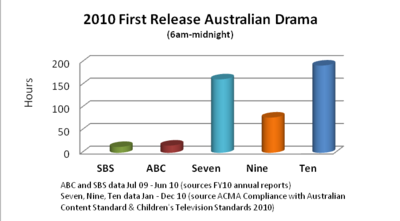

GRAPH 5: Comparison by network of first release drama. This graph is prior to the very recent increase in first release drama on ABC-TV, and decrease on SBS-TV. (click image to enlarge)

The only way SBS can now fulfil its Charter obligations is for government to provide more funding, given that advertising is not sustainable.

Conclusion and recommendations

If comparing SBS to Australian commercial broadcasters, or to public broadcasters overseas, or only the ABC, the SBS is very underfunded.

Even without comparison to other Australian broadcasters, SBS is worthy of an increase in funding due to its unique role within Australian society. The cultural worth of SBS deserves nurturing. In the context of the SBS social inclusion and social cohesion policy and the whole of government’s Social Inclusion Principles for Australia, such policies can only be achieved with a combination of greater government funding and a withdrawal of advertising disruptions on SBS.

The changes in SBS over the past five years that led to public outcries ought not detract from the inherent worthiness of the world’s first multicultural broadcaster, SBS. With sufficient government funding, it has a rightful place in Australian society and is crucial to the success of a socially inclusive society that embraces all cultures of the world, settling within Australia[86]. However the unhealthy obsession that essentially grew out of an instinct to survive, namely the commercialisation of SBS with the continual disruption of commercial breaks in SBS-TV programs requires ‘fixing’ with the same hand that provides an increase in government funding.

Five years ago it was speculated that after a period, people might accept the in-program disruptions. All the evidence since then has proved the contrary [87] [88] [89] [90] [91]. There are a growing number of electors who would support government funding to end in-program breaks on SBS-TV through legislative change as a matter of priority.

- It would be highly desirable that on 1 July 2012 base government funding be increased by at least $45m[92] for the specific purpose of removing in-program breaks; all disruptions on SBS television programs would cease – adverts at the beginning or end of a program remain.

If the above funding was not available there are other options.

- Government appropriation be increased by at least $15m each year for three years ($15m × 3 = $45m) for the specific purpose of removing in-program breaks, to be commenced by the SBS, either:-

- on a pro-rata basis in each year of increase referred to; or alternatively,

- allow the SBS to postpone the cessation of in-program breaks until the third $15m increment had occurred i.e., when the full $45m of increases had eventuated, (2014-15) and cease all in-program disruptions in that year, e.g., 1 January 2015.

If neither of the above options were available, then the following would delay the desired action pro-rata with an overall total lower cost, to a period when the economy is stronger than during a period of deficit.

- In program breaks cease on 1 April 2015, i.e., in the last quarter in the final year of the forthcoming triennial period, and government appropriation be increased by approximately $11.25m[H] in the 2014-15 financial year ($45m ÷ 4 = $11.25m).

This may be the least preferred option but would nevertheless ensure better financial security for SBS at the commencement of the 2015-18 triennium (outside the scope of this submission) .

As a step towards the above, the following interim measure might also be considered.

- A reduction of in-program breaks from the current number, while still allowing one only in-program break per program (plus the break between programs). Such action has not been claimed by the SBS as having an affect on ability to raise advertising revenue. Our modelling confirms this.

Whilst the above dot point is not ideal to the viewer, it would be better than the current model of numerous in-program breaks (2 in a half-hour program plus a break after, and 3 in a one hour program plus a break after[93]). The suggested approach above would reduce the frequency of disruptions yet still accommodate some in-program breaks in addition to ordinary breaks between programs. It may be low cost or revenue neutral and help to justify other funding initiatives.

- In addition to the funding above for the specific winding down of in-program disruptions, additional funding as required for the SBS to carry out its other initiatives.

The intrinsic social value alone of SBS would qualify it worthy of a substantial increase in government funding, and particularly funding for the removal of in-program breaks.

The principles of social inclusion and cohesion referred to earlier are a whole of government policy[94] [95] [96]; that being the case, the rightful execution of such policy alone would also be justification for a greater level of public funding to the SBS than has previously occurred, to properly implement initiatives identified in this submission.

In consideration of our findings, Save Our SBS Inc recommends that funding for SBS in the 2012-15 triennial period be increased with specific funding granted as a priority for a reduction and removal of disruptive breaks in television programs, with a longer term plan to free the SBS from a reliance on advertising.

This submission is published at https://saveoursbs.org/archives/1993

scan the QR code above with a smart phone – to read this submission while mobile

Notes and References for this submission are here.